Claire: Hey, listeners. Claire here. The episode you're about to hear is actually a panel discussion from the annual conference of the Association of Performing Arts Professionals we recorded it live on January 16, 2023 and cut it down a bit for your ears today. The panel was called "Stop Talking. Start Listening: Finding Common Ground with Young Arts Workers and the Future of Our Field." I am so excited for you to hear this great conversation, so let's go live to New York City.

You're listening to ARTS. WORK. LIFE. a podcast from APAP, the Association of Performing Arts Professionals. I'm your host Claire Caulfield here with a special bonus episode from the APAP conference in New York City [Applause]

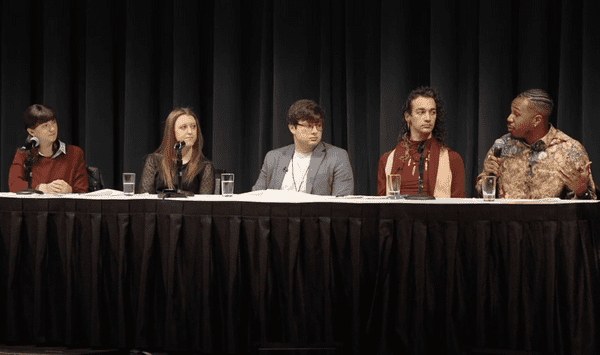

We have an amazing group of young arts workers here who are all under the age of 35 and they've bravely agreed to share their candid takes about their experiences to help the entire industry create a more sustainable future and with that I'm going to let our panelists introduce themselves.

Lexis: Hi, everybody. My name is Lexis Hamilton. I am the presenter and program coordinator for the University of Wyoming located in Laramie, Wyoming.

Bobby: Hello everybody my name is Bobby Cento, my pronouns are he/him. I work as a booking agent for Ed Keane Associates.

Javier: Hello, hello, hi, everyone my name is Javier Stell-Fresquez. I use um all pronouns and I am I'm Performing Artist as well as a producer of festivals.

Tariq: Good morning, everyone, Tariq Darrell O'Meally here. I work at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at the University of Maryland. I'm a part of our multi-cutorial programming team along with uh the creator and curator of the Blacklight Summit.

Claire: Lovely and my first question today is for Bobby, but I hope the other panelists will jump in in with every question. Bobby, there's been a lot of hand-wringing about how young people just jump from job to job and they don't have any loyalty to their employer. Have you seen this kind of job hopping, if you want to call, it um why is this happening, and how can organizations respond?

Bobby: Yeah, definitely, Claire, I've seen through peers and colleagues and friends and hearing their stories.

I think the the overall theme that a lot of them face is the rising cost of living not only with that, but then cost of tuition and loans and things like that. It's a big driver for people especially young people to feel the pressure you know to need to not necessarily feel like they need to stay in one position for more than a couple years at a time, so that's definitely a big thing I've seen, and becoming a trend you know in this kind of labor culture that we see today. And in terms of things that organizations can do to address it, it can be a variety of tools and resources that they can provide one of them just providing a more healthy work-life balance. It shouldn't be expected that to find a healthy work-life balance is going to be the exception it should be more of the norm and I think people are looking you know to not necessarily settle for something that might be not providing them you know the best work-life balance, or the most freedom to you know to do what they still need to do to live a happy and more importantly healthy life but you know to also know that if that is not something that they can achieve at the current uh in the current situation that they're facing that they can still find that somewhere else and that that opportunity can still be existent for them somewhere, so yeah.

Tariq: Without going too deep into the minutia, I think uh when we're talking about Millennials and Gen Z which is way more aggressive than anything we've seen previous in a way that's kind of beautiful is that we're without the illusion of the American dream, so when we're talking about we're we're leaving jobs because we don't. The planet feels weird and we don't know that we have 10, 20 or 30 years to completely invest into a thing or like retirement or doing things like buying property or so I think without the illusion of a dream to that this will ultimately pay off it's becoming clear that it might not and that makes it difficult uh in the uh morale like morale is down so like if you want people to stay at your job it's a human being and um you know, so much a performance. I come I'm a dance predominantly in dance and so much of the work used to be "leave it at the door" and that's just disassociation, so it feels like the farther apart, we got the more integrated we become with our feelings, so I just think uh it's about um not per se another dream but like building uh useful realities. [Applause]

Claire: And that segues even better to what I wanted to ask Javier about. When we were talking earlier you brought up this idea of scaling down. Can you explain what you mean by scaling down and how organizations might be able to implement that idea?

Javier: Sure, hello, absolutely. In order to answer this question I think I need to give some more context to where I'm speaking from. I am based in the Bay Area, and I make work there primarily with Indigenous communities. I've worked with non-profits of the scale of let's say an annual Festival producer, larger Dance Festival producer and smaller. At that scale at least it really feels like there are so many folks with the illusion that if they do more it will be better. They will make more grants they will be able to demonstrate a greater impact. And more and more I'm just really if anyone approaches me for collaboration or for consulting, that's often the first thing I will check on. Are you, have you downscaled in the last few times that your budget dropped? Have you absorbed the shock that it sent your team? Have you taken care of your team when you had to cut the team short? Or did five jobs get piled onto one pair of shoulders?

And I also just want to say that within our field especially I just want to name prolific, lifting up an artist that is prolific as one of the virtues of what an artist needs to be, there's a way that the idea of product over process is really really drains the artists that we all rely on, and that we want to be supporting hopefully for their next step, not just their engagement with our organization. And I think yeah just trying to switch overall to a culture and an ethic of care versus maximal productivity can allow us to be, to respond to the fact that the newer generations are aware and have the language around, what is the space that is just trying to extract labor from me as much as possible.

And with like there's all kinds of labor to consider in that there's like there's the emotional labor of a person uh who is not of your work culture or doesn't quite fit in immediately um who then has to either code switch because they're coming from a different ethnic culture um or from a different class background in order to be able to produce with the team, to be a good team player. I'm putting all of these in air quotes because I really think that we should interrogate them more how we think about these things from the hiring table to dealing with conflict in the workspace.

Then there's also just yeah simply putting too many jobs on a single person and not asking the question what's the truly bare minimum we can do to just at least keep operating. A really easy example is social media like your young interns or your young staff when they come on board just because of their youth or because of their relative skill with social media does not mean that they should even that they should even necessarily be suggested that they be the social media manager. That is a big job, and it's a huge responsibility to take on the voice of an organization.

I will oh one more thing one more thing that I really wanted to lift up about that as a festival producer is the annual festivals are definitely also unsustainable for most of the presenters that I see in the Bay Area. But I just want to say that I really appreciate um when a festival takes its time to know and to approach with intention each of its years and its team each year. There are quite a few festivals actually that have asked me to work with them, but because I know their team is stressed because it does not get off the annual frequency rhythm, I have turned them down, so yeah. [Applause]

Claire: And it seems like the thread there is a call to really approach the work with being super intentional and not saying that we can be all things for all communities because every time you reach out a hand to a different community, they have different needs they have different wants and they can tell if maybe you're

virtue signaling or just parachuting in for this one play or this one performance and then leaving. Does anyone want to pick up on on that thread of when they've seen a lack of intentionality in some of their some of their work?

Tariq: We're really trying to figure out how to interact with all of the things that for you know 30, 40, 50, 60 years that people swallowed, so um our emotional intelligence and the the desire to respond really turns into a reaction, and I think sometimes comes from a place of fear, so in order not to be um uh the now appropriated cancel culture, which was like something like black people used to use, but now we're like everyone's being canceled, um to try to really figure out what's the best way for us to move forward. But my good friend Shanice Mason who's working with APAP who says all the time, I don't know if we're asking enough questions and I don't know if we're asking the right questions. So and when you're talking about scaling, we didn't get here overnight so it's going to take a little bit of time and pacing and iterations and not to, I don't own a house, I rent, but I assume you can't renovate the whole thing at the same time and living it well, so what pieces can you and increments take care of without feeling crushed by the necessity to be better. So it's kind of like a brick, brick by brick, I think.

Javier: Yeah, I think transformations take time and if you want to be if you want to be in pace really with the transformations that are happening around you in the field and in society I think that that requires scaling back what you produce, so you can do the work internally.

And land acknowledgments. They're definitely one of those virtue-signaly things um that uh I have been tasked to ask people frequently, "Why are you doing them?" Keep asking yourself, "Why are you doing them?" This is a question coming from an Ohlone culture-bearer who kind of championed the use of land acknowledgments in the Bay Area a good probably for the last full decade, and when she sat with um myself and the director of a theater there that I produce a festival of two-spirit performance at, she I made sure that the director was was there at the conversation for this conversation about land acknowledgments and she just opened up the question as to why. And the different Indigenous people in the room had full answers and the director not so much, but they really heard what we were saying, and they immediately put into practice some of the deeper principles and the deeper whys for Indigenous people of using a land acknowledgment. They put that, the director themselves, put that into practice at our festival and got vulnerable. That's one of the biggest things about that learning process that I can hand off, get vulnerable in that process of asking why. [Applause]

Claire: Do you think there's a generational divide in how we see virtue signaling or seeing community outreach efforts?

Lexis: I'm gonna jump in on this one. I think yes I think we tend to be more self-aware of what's going on in society.

Claire: And when you say we, what group is that?

Lexis: We as young arts workers and people in our fields. I think we're more aware than some of the older as you would say experts in our field and know what our communities should need. I'm speaking from a Wyoming place where 90 percent of our community is white and doesn't have a lot of cultural representation, so for groups that like we bring in as a presenter...

Tariq: Whiteness is a culture.

Lexis: No, no, you are correct, it is. But I'm just saying other cultures besides the white culture as well. We try to bring in groups that have different uh different knowledge and they can bring something new and refreshing to our community that they need to see.

Claire: And how do you do that intentionally and without it being exploitative or to build something?

Lexis: I do, we do not book groups that play up to the stereotypes of whatever culture that is, if that answers that question.

Claire: And if you have a mostly white group who is planning these performances or deciding what is a stereotype and what isn't, how do you navigate that?

Lexis: That's a challenging question. Since I am white, I ask other people of whatever, so I'm just using this as an example and we want to bring in like a LatinX group, Mariachi group, I'm not from that culture, so I'm going to ask and be reassured by someone from that culture that this isn't like virtue signaling, and it's not a stereotypical performance of what you should be able to see to market to a white community because you don't want that, right? So we just have to rely on other people.

Claire: And a lot of arts organizations might have tight budgets in that role where you're reaching out for someone for expertise, is that a paid consulting position? How do you deal with the labor that they bring? [Lexis] Connections in your community that's the best way. I think that's the best way to get an honest opinion.

Javier: Yeah thank you thank you for that thread of questions. I think um more and more that kind of labor also needs to be valued um much more highly um the moment that someone is translating their culture or to answer the question of are we the right people to be putting on this performance um yeah the moment that conversation starts, the person whose culture is being desired is often doing a lot of work. That's an incredibly valuable skill that too often is not immediately compensated, and too often people think that it's okay for that to be the last thing in the budget. Visibility is not enough. So yeah so just pay people for the work that they do, all of it. [Applause]

Claire: And that pay is a good segue to a question that I wanted to ask Lexis about. I know that you've had the experience where you're maybe working two or three jobs or you're the only one in your department. What's that experience been like and what changes would you like to be seeing in the industry?

Lexis: I feel like I'm not alone in this sentiment that as a young arts worker, our generation, we're just go go go and very ambitious all the time, so sometimes that ends up morphing into a couple jobs that after the Pandemic those people have left or they were laid off and all of that gets piled on to your hands. And we mentioned social media earlier, if you give suggestions about social media like, "Hey we shouldn't be writing essays on a Facebook post that's just, nobody has the attention span for that."

Tariq: Or using Facebook.

Javier: I still use it.

Lexis: Facebook, Instagram, all the things, and then they take your suggestion, as like, "Oh well, then you can do it better" and so now that has been piled on to your position, so it's just the awareness of we can't do it all. We want to, but we can't, and it's very hard.

Claire: What do you feel when you hear that idea of young people shouldn't be advocating for more work-life balance or higher wages because this is our time to pay our dues?

Tariq: it's not the same equation. We've lived through a series a financial crises, perhaps the end of the world, I don't know. There are a lot of like exacerbating circumstances and not that this needs to be like the suffering Olympics or comparative analysis it's just, what is, I'm reading of, that's a lie, I'm listening to Viola Davis's memoir, and something she says is like um not, basically I'm paraphrasing her, not having options is what it means to struggle. And paying your dues is a kind of a thing. It's just running for seven days a week and not having the savings and having to work three jobs at your job and then an additional one in order to make things work will change how people are feeling, and then if there's no um release or no respite, and you're like, in 20 more years um during the great flood you will be okay. It's like that that's a hard sell. I don't know.

Javier: I'm loving the apocalyptic imageries. I'm really here for them I wish that I wish I could join you on that frequency, but it's too early in the morning for my brain. But um I I think that that's like that logic that set of logics around paying one's dues um I think maybe ask yourself if you find yourself saying those kinds of things or thinking those kinds of things about a young worker in the space, um what discomfort, what resistance to change, what resistance to growth that might be coming from the expectations around their youth um or the thoughts around their youth of projections from you and from the work culture onto their youth.

I think um so stereotype threat is, for folks who don't know, it's uh the anticipation and the work you have to do anticipating people stereotyping of you. And that can be along any kind of identity category. And of course it's worse when you're of a more marginalized class where the power dynamic does not favor you because if you do fulfill the stereotypes in those situations that often undercuts your legitimacy, your safety, so just having that kind of stereotype threat and that kind of cognitive dissonance around, "Oh, I am the youngest person in this team, but I don't want to come off like all these things that I feel being projected at me, so let me pretend to be different or let me assimilate harder into this work culture that, oh by the way, burning out everyone else is here, so how am I going to do a different thing?" All of that that, all of that stereotype threat, labor gets in the way of even doing the work that you need them to do. And that's true of every kind of stereotype threat. It's like how um Toni Morrison who says uh racism's primary function is to distract us from the actual work that we have to do or the actual... [Applause]

Yeah and so it's very true of ageism as well. So yeah I think if we can just be present with the workspace, and think critically about what professionalism entails, and ways of performing it, and narrow ways of gendering people, of expecting them to be of certain class background, the ableism that's in that too, all of that I think comes out and comes becomes very clear when you interrogate things like professionalism, with with which ties into classism, which ties into paying your dues. [Applause]

Tariq: And among all of the things that we're experiencing right now, the class issue's real distinctive. If you're coming at an entry level position uh paying your dues to stay exactly where you are feels weird. Like, nobody's budget is increasing, like and you're just like you will be at um you know 45 um until the dawn, until we come back again, so it's I think the class issue. And I also want to offer the point of this conversation is to, at least for me, to like really emphasize the the interior experience of people, if you're not a young arts professional, that's going on. And like the real kind of adversity, especially being and consistently justifying being in the arts, when we know that um there's kind of a siphoning off of resources. It makes it more difficult, and you just see the gap getting wider in all of these different things. It just makes it uh hard to lean in, and hard to like show up and continue to do the five jobs, if you're just it's like, oh is this, I think, someone like a Sisyphus reference. I think someone said, here you know the boulder just gets bigger each time it rolls down the hill, so, yeah.

Claire: We've thrown out a lot of big ideas, a lot of suggestions for change. Do you think that the industry is open, willing, wanting to change?

Tariq: Um short answer no not really. I think we're in love with our limitations. There are certain things we're like, "Wow, this is really not working. Hey, Jack, do you want to go to the bottom of the ship and sink with it?" So I think there is the, now I'm being like uh you know snarky, but genuinely, I think the desire's there, but all magic has a price, so if you want this to do this, you have to you have to give something back, exchange something. And I think that's a kind of a hard thing to negotiate, coming from dance, you know, your your muscle memory is to respond to a thing in a certain way, so if you are not actually, if you're not vigilant in your practices, and your intentionality, and your scale, it makes it uh difficult for anything to shift. The, I would say, I'm coming from concert dance, I think we're in a bit of a identity crisis. In that existential crisis is making us, um we don't know what to do next because we've never, I'm not going to say never, I've only been here 34 years, I don't know what never means. It's difficult to really figure out, look at yourself, and understand "Ok, if the emperor doesn't have any clothes, how do I start sewing the garment?" I guess.

Claire: I think we're collecting note cards right now, so final thoughts before we get into audience questions?

No, okay I'm going to read these really quickly then um. Ok, so here's a great question, Gen X workers were used to being worked to death in the arts, younger generations aren't willing to accept that, but how does Gen X feel empowered to now follow the new rules our arts or just assuming that Gen X will continue to pick up the extra slack while younger generations demand better work-life balance? Whoever wrote this, That's heavy.

Tariq: We're, we're all in the same thing. I mean not literally the same thing, but picking up the slack. The bill is due for everyone. Like everyone is feeling the impact in a different way, and I think um healing is difficult, um I think uh what is the thing I wrote down earlier uh that perhaps healing is unafraid of facing fears and pain. Perhaps healing is not always the absence of pain but the understanding of it. So I say that to say like perhaps the goal is for um to be inspired by um the younger generation open quote, end quote, the uh you know 30-plus years of people beneath you, to make a different, a different decision um Meshell Ndegeocello said, you know, another day to try. So like activate your power in a different way. Instead of it being like, "Well, they're doing this and now with now I have to pick it out" because um in some instances, we're not choosing to participate in our own degradation.

Claire: So that conversation on how we bring generations together segues with this great question. How do we find common ground with older workers to break those limitations wide open and where does the responsibility lie to approach that conversation?

Tariq: I want to offer that the division is the mission, like this is this is the game, right? Like our country is becoming more and more polarized, it's either you, it's either this, or it's that there's no, when um not just in a gender way, when we're talking about binaries we're we I think the the conversation around is talking about a spectrum of experiences, so like it's going to take everyone to kind of figure this out. So instead of like not allowing this group of people to like activate their power collectively, we will siphon off resources, we will do this and laugh at you. It just has to be more of a dialectical experience than a didactic like this is, it's either this or it's that I think it's dangerous.

Javier: Yeah, I'll add um I think my simple response to this whole thing that we've opened in terms of age differences that the children are sacred and that the elders are sacred and the both is true and um building more and more horizontal and circular spaces to hold the fullness of the team um shows everyone how to not just get along but actually appreciate what the others is bringing. And with that um to get out of binary thinking to get out of the capitalist notions of not ever having enough, of having to generate having to generate more and more, and that there is scarcity all the time, and there will never be enough time, and we have to pack our time. The energy we also have to put into disinvesting from a lot of these structures that then make it so hard for us to imagine new ways.

Claire: Great and our last question before we have to say goodbye for today is what do you think that we, parentheses especially those with decision-making power, will have to sacrifice or completely let go of in 2023?

Tariq: We're not in a reaping season. I think the the productivity, we're saying we're back, but it's kind of like, not really. I think um we've just gotten out of like surgery, and we're in the ICU right now so the the the pace in which we um are going to move at it's going to take some time if we don't want it to crumble you know at the slightest uh blow of the wind. So I think um the pacing is important, and I think um understanding that we're planting and that it's going to take some time it's going to take care, compassion, practicing our courage. What will next year bring? I just think it's um being purposeful and understanding that this is going to take some time because this is like systemic things and also that is going to look different in each organization, each position, but it it's about beginning the practice and being vigilant, but I just think pacing and being even better at having a vision. If we're not better about visioning the experience, truly the world that we want to do create and what the actual steps to produce that like we would put a tour together, none of this is going to work.

Claire: On that note, it seems like we're wrapped up for today. Thank you so much to our panelists. [Applause]

>> music

We covered a lot in that episode, and we're going to continue this conversation in the next bonus episode of ARTS. WORK. LIFE., we'll answer some questions from the audience that we didn't get to during the panel and reflect more on the experience of young arts workers.

>> music

Thank you for listening. ARTS. WORK. LIFE. is a production from APAP, the Association of Performing Arts Professionals. APAP is the national service organization for the performing arts presenting, booking, and touring industry. You can join APAP at apap365.org.

I'm Claire Caufield, your host and producer. Jenny Thomas is our executive producer, and our music is from Blue Dot sessions.

This podcast wouldn't be possible without the generous support of the Wallace Foundation, so thank you.

Other thank you's to Willie Santiago for organizing this great panel that you heard in the episode, Buoyant Partners for the on-site audio recording, the APAP staff and board of directors, and the hundreds of thousands of arts workers across the world.

Your stories matter, and arts workers are essential.

Speaking of stories, Season 2 is coming this summer, and if you work at the performing arts field, we want to hear your stories for this podcast. Submit them at artsworklife.org.

And if you enjoyed this episode, which I hope you did, please leave us a review.

It helps other people find the show.

>> music

Carolyn: Arts, Work, Life. that’s real *laugh*

>> music

END